Interview with Greg Wilson

Wednesday, November 6, 2019

by Tat

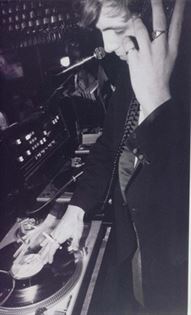

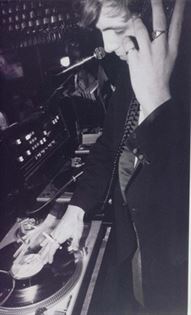

As far as longevity behind the decks goes you would be hard pushed to find a more loyal servant to the cause than Greg Wilson. With a career that will enter its sixth decade in 2020, Wilson is a much respected pioneer who brought turntables from out of the nightclub and radio studio onto popular live TV to show beat mixing for the very first time in 1983. Starting his career at the age of just 15 in 1975 he soon built up a reputation as a knowledgeable and technically gifted DJ playing at notable nights at The Wigan Pier and Legend in Manchester. Despite taking a break from DJing to pursue music production and management, Wilson’s status as a bonafide legend in the DJ world was confirmed and highlighted with a superb return to the fold almost two decades ago. Since then Wilson has added to his reputation with excellent edits, live sets and shows and a taste for Dischordia.

No doubt you are often asked about your appearance on Channel 4’s The Tube. How did you feel being in such an environment when until then the only DJ we’d seen on TV was celebrity ones?

You saw radio DJs on the TV, presenting Top Of The Pops and other programmes with music content, but club DJs were very much in the shadows in those days and mixing, from a UK perspective, still in its infancy.

When I was on stage at The Tube and they were counting down from 10 seconds to live was perhaps the most scared I’ve been in my entire DJ career. The realisation of how much was at stake, how stupid I’d look before my contemporaries, not to mention the general TV audience, if I messed up – there’d be no take two. Then there was the case of the guy with the handheld camera who I was terrified would knock the decks, where the records were cued up waiting to go (he did actually bang the deck when filming, but to my eternal gratitude the needle didn’t jump).

Once I’d started I was fine, I kind of went into automatic and it all passed quickly without a hitch, but it was that waiting period beforehand that gave me the heebie-jeebies.

YouTube clip of Greg on The Tube

Photo by Nick Mizen

Photo by Nick MizenThese days DJ culture is very much embedded in UK psyche, so at what point did it hit you what a huge thing it was to be the first British DJ to mix on television? Do you think people got what was happening?

If you watch the footage you’ll see that most of the audience seem somewhat disengaged or bemused with what I was doing, DJ culture, as we now know it, still essentially underground. I’d imagine that most of the people there had never heard of mixing, let alone seen how it was done.

I suppose that I’ve only realised its full relevance since the internet came along. It was only shown on the TV once, and at a time when not everyone had VHS recorders, so, although I got lots of props from the DJ community and the people who came to my clubs, it didn’t have any big immediate impact on my career. I was more a curio than anything else for the majority of people who’d tuned in.

At that time you were playing at all dayers which were part of the scene’s fabric, these were essential hubs for soul and hip hop fans, why do you think they became less of a thing across the UK?

There were other factors to its demise, but the final nail in the coffin of the all-dayer scene was the arrival of the rave era with its warehouse spaces and illegal parties. Hip Hop, House and Techno took over from the music of the previous years, Electro-Funk, Boogie and Street Soul. Electro had provided a break from the traditional Soul/Funk scene, so the momentum towards the new was already in place, with all-dayers, and their associations with the Soul and Jazz-Funk scenes, less relevant – it was a case of ring out the old - bring in the new.

Like many music fans and DJs they have their epiphany moment where something happens that changes their whole musical direction? Did anything like that happen to you back then or even now?

I went to a club in Essen, Germany in 1980 where the idea of mixing, in the right context, really crystalized in me. It was a great small club called Librium, I was on a two month contract at a club in nearby Mülheim and I went there on one of my few nights off. I’ve since deducted that the DJ was probably Peter Römer, who is acknowledged as Germany’s first mixing DJ – I now know that he played at Librium around this time, so it would make sense. Anyhow, although I’d seen the Argentinian-born American DJ Greg James, the first proper mixing DJ in the UK, at The Embassy Club in London a few years earlier, it was this night in Essen that really resonated with me. At that point nearly all clubs here had belt driven turntables unsuitable for this new mixing fad, as many DJs regarded it, but over in Germany, for the first time, I was working with SL1200s, the German clubs were far more advanced technically. I really liked the way the DJ in Essen was putting it all together and resolved that, in the right circumstance, I’d place the emphasis on mixing.

Photo by David Lubich

Photo by David LubichI went back to the UK to take up the residency at Wigan Pier, which, when it came to sound and lighting, was so far in advance of anything I’d previously come across here. They didn’t have 1200s but I worked on Technics 1500s, which were also vari-speed. I began to alternate more between microphone and mixing at Wigan Pier, perhaps playing two or three tracks continuously before back announcing. The microphone and how the DJ used it, was still vital, but when I took over the Wednesday Funk night at Legend in Manchester in 1981, which was owned by the same people who ran the Pier, this seemed the to be the environment I was waiting for, with a predominantly black audience seriously into their music and dancing. Legend had three SL1200s and sound and lighting that even surpassed Wigan Pier. I left my Wigan Pier residency to become a black music specialist, only playing upfront black music, as we called it, mainly US imports fresh off the presses and supplied by a small amount of specialist shops, Spin Inn in Manchester being the North’s port of call. I retained the Tuesday at Wigan Pier, where I’d play similar tracks to Legend on the Wednesday, and these would become the top two nights in the North, right at the very cusp of the scene, especially when the new Electro-Funk music emerged and these state-of-the-art venues provided the ideal setting for this futuristic sound. Electro-Funk was also drum machine based, making it far more mixable than tracks with a real drummer.

It was all very fortuitous - I was in the right clubs at the right time with the right crowd, playing a new type of music that you could only hear initially in this underground environment. That night in Librium had primed me for what could be, and I was ready when the opportunity presented itself.

As someone who has bookended Britain’s contemporary dance and black music scenes, looking purely at the dancefloor and DJ booth (beyond the technology) what would you say are the most striking changes between the early 1980s and 2019?

I’m no longer a black music specialist playing the latest music available, but more of a connector, bridging the past to the present with the help of reworks and re-edits, along with the addition of contemporary tracks that fit this vibe. So my role as a DJ is very different from what it was. Back then the audience I ended up playing to where at the cutting-edge – when you talk about the dancing in clubs like Legend and the Pier you just can’t compare with now. For many young blacks it was everything – in their day to day they might have nothing, but if they had a reputation for the moves they could pull off on the dancefloor, they had status within the community. It was serious stuff – there was none of the hands in the year party vibes that you see now, this was all about getting on your groove and getting down. Whereas people might now say on a good night that the dancefloor was jumping, back then, in those underground clubs, it was pulsing. Things worked on an altogether deeper level.

Photo by Nick Mizen

Photo by Nick MizenAs for the booth, when I started off the DJ was often hidden away in a darkened corner. Most people wouldn’t have known who the DJ was in most mainstream clubs, there used to be a saying used by club managers that ‘DJs were ten a penny’, they certainly weren’t valued in the way they would be later. It was different on the specialist scenes like Northern Soul and Jazz-Funk, where the DJ line-up was all important. To give you an example of our worth, when I started in ‘75/’76 I got £6 per night, I’d later work my way up the pay scale until by the end of the decade I was getting £20 a night, which was well above the going rate. The Wigan Pier residency more than doubled my nightly wage, but when I established myself on the all-dayer scene I’d pick up £100 for an appearance, whilst I worked out a sliding scale based on numbers through the door at Wigan Pier and Legend that cut-off at £75 per night, which is what I took home most weeks.

I was very well paid back then, relatively speaking, earning far more than most of my contemporaries, but it’s a world apart from now, where DJs can, of course, command huge fees. Now the DJs are very much the focal point, centre stage rather than hidden away, so, more than anything, the most striking change is in terms of status.

You’ve released three Credit To The Edit compilations, have you any plans for a fourth edition?

No, but never say never. I never expected to do a Vol 3 but the opportunity presented itself and enough time had elapsed since Vol 2 to give me the edit options I needed to compile another compilation.

Edits have been commonplace, how easy is it to spot the wheat from the chaff and do you feel we might at some point suffer the same fate as Northern Soul where the source material ran dry, or do you think it can keep building upon itself?

It’s a process to sift through everything - I’m pretty fussy about what fits my criteria, but there’s no hard and fast rules, although my ideal is a respectful rework of a track I know from first time around that it’s difficult to mix in/out in its original form, perhaps with added kick/bottom end boost to give a sonic makeover. I take your point about Northern Soul, but the Disco era and early-‘80s is still fertile ground – if it wasn’t I’d have playable reworks of all the tracks I used to play between ’75-’84, before I stopped first time around. I think this cut and paste ethos is now a fixed part of the landscape, so I don’t expect the re-edits scene to dry up anytime soon – it’s more a case of trawling through the quantity in order to keep unearthing the quality reworks.

The last decade has seen the DJ and producer role become incredibly intertwined as well as label and club owner. We now rarely see people who operate purely in the realm as DJ at the higher level. What qualities do you think a producer needs to be a good DJ and visa versa?

I think the two roles are quite different in essence – a DJ works in a live environment where it’s all happening in the moment, with instant feedback from the audience, whereas a producer locks themselves away in a studio, often alone, capturing musical moments that they proceed to listen through continually for days, weeks, sometimes months before the resultant track emerges. Some DJs just don’t have the aptitude for the repetitive nature of the studio, whilst some producers would be terrified if you took them out of the studio and put them in front of a crowd. So, although there are many examples of people successful in both areas, it’s not something that necessarily goes hand in hand.

Photo by Ian Tilton

Photo by Ian TiltonYour Super Weird Substance label came back to life last year, what plans are there going forward for it?

Sometimes it’s difficult to juggle the various aspects of your career, and SWS has been on the backburner for a little while as a consequence, but we’re now almost ready to properly re-launch with a cluster of new material.

You and Kermit (Ruthless Rap Assassins) are both involved in the Discordian counter culture movement and DJed at both of the Festival 23 events. How did you come across the movement and collaborate with Alan Moore?

Yeah, a bit of chaos is good for the soul, although there comes a point where you need to restore a bit of order! Kermit is a big comics fan and had, for a couple of decades, been trying to get me to read Alan Moore (me not being a comics reader). I finally engaged with his work early this decade and was absolutely blown-away - Alan’s rich storytelling and substantial wisdom, especially in the documentary film ‘The Mindscape Of Alan Moore’ (2003), really helped me make more sense of a lot of stuff (this is where I heard the term ‘super weird substance’). We went to see an event he was speaking at in Northampton University in 2015, with counterculture the central subject, and that’s where we first got to meet him. John Higgs, the author, was the Discordian catalyst – I’d invited him to speak at our Super Weird Happening in Liverpool having read his wonderful KLF book. John knew Alan, so he made the introduction, and it was also via this route that I came to meet the Festival 23 crew.

In 2016, on the day of the Brexit result, the newly-formed Northampton Arts Lab happened to be holding their inaugural event, ‘Artmageddon’, which we attended, and Alan, complete with mandrill make-up and, as ever, with his finger on the pulse of political developments, delivered his ‘Mandrillifesto’ that night, unleashing this ‘dictatorial baboon’ on his Brexit-stunned audience. Kermit was cheeky enough to ask him whether we could do a track using his words and he agreed. This ended up becoming a mixtape, the backing, which I’d edited up, being various monkey related tracks (‘Monkey Man’, ‘Funky Monkey’, ‘Monkey Spanner’, ‘Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey’, ‘Apeman’ etc). The samples I used were also on the same theme, so it was great fun to put it all together. Kermit and singing duo The Reynolds did a great job of fitting Alan’s words to the music, and, on hearing the finished result, Alan was delighted with what we’d done. The final flourish was to get Alan, as The Mandrill, to take the role of a radio presenter on station KONG 22.3, which he pulled off to perfection with the presentation flow of a natural. All in all it was a hugely enjoyable project to be involved in, and a great successor to the ‘Blind Arcade Meets Super Weird Substance In The Morphogenetic Field’ mixtape, which had kicked off the whole process for the label and included a sample of Alan saying ‘information is a super weird substance’, 18 months before we met him in person.

Alan Moore's Mandrill Meets Super Weird Substance At The Arts Lab Apocalypse

gregwilson.co.uk

Find quality music first with Trackhunter